World Suicide Prevention Day – Sat 10th September

Globally suicide remains a leading cause of death – ahead of

deaths from malaria, road accidents, homicide,

malnutrition, natural disasters and even war, yet few countries have been able

to reduce their suicide

rates. In all countries the suicide rate for men is twice as high than for women and in some countries it is even higher.

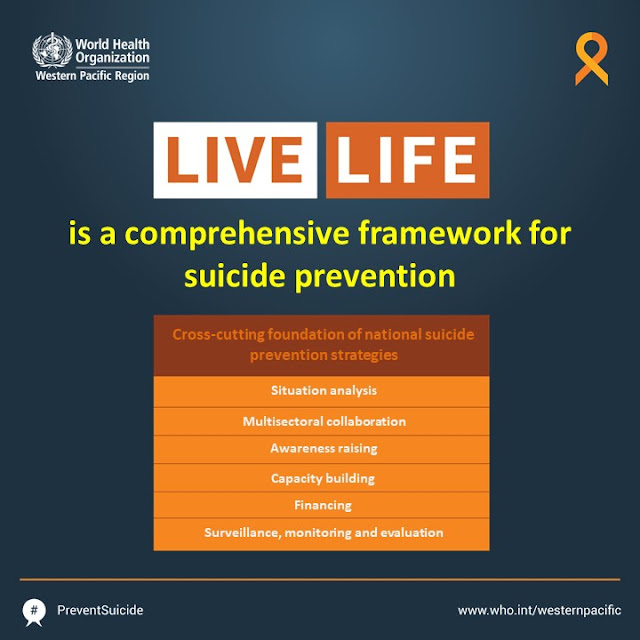

I’m not going to write a great deal about this today. A great deal has already been written. See for example the very detailed suicide prevention strategies which have already been published as part of the World Health Organisation’s LIVE LIFE Campaign, aspects of which have been successfully implemented in a number of countries. The suicide rate does vary greatly however both within and between countries - by culture, by religion, income levels and gender, so what works in one region may not work in another, but what seems to be lacking is not so much the how, or even resources, but the failure to make suicide prevention a priority and to have a coordinated approach.

Developing National Prevention Strategies

The first part of the WHO program - the LIVE aspect, is a ten -point toolkit to help countries to establish and implement their own national plan starting with how to analyse the problem and bring all stakeholders together, right through to monitoring, evaluating and reporting on what worked.

Specific Ways to Reduce Suicide Rates

Part II of the WHO’s program -The LIFE section is about ways in which to reduce the incidence of suicide in general. Just as detective stories rely on key points such as MEANS, MOTIVE and OPPORTUNITY, it has four key features. We’ll look at each of these in turn.

1. Limit access to means

2. Interact with media to create awareness but ensure responsible reporting

3. Foster Socio -emotional skills in schools

4. Early Identification, assessment and follow -up of anyone affected by suicide.

1. LIMITING MEANS

Suicide is often a snap decision in the light of some negative experience. Many people who attempt suicide but survive, report that if they’d only had a moment to reflect on what they were doing, rather than reacting in the heat of the moment, then they would never have tried to take their own life. This highlights the need to remove readily accessible means. A few examples follow. The WHO pages have many more.

-

Restricting firearms has

been effective in a number of countries including Australia, the UK, Israel and Switzerland. A recent Danish study

confirmed that restricted access led not only to lower suicide rates from that cause, but in most cases to lower rates overall. Denmark has had a declining

suicide rate for the last two decades. In the USA whose suicide rate is particularly high, firearms account for 60% of the deaths, or more than 24,000 people, twice the homicide rate, 10 times the European average and 30 times higher than the UK.

- In low to middle income countries, availability of pesticides has been linked to high suicide rates, so restricting access to them has been effective in a number of Asian countries including Fiji, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and the Republic of Korea. South Korea’s ban on paraquat not only contributed to a halving of suicides, but has not resulted in any reduction in crop yields, thanks to a program which encourages the use of less toxic alternatives and the promotion of organic farming.

- South Korea has long had closed safety glass doors in its subway stations – particularly near universities and schools. These doors align precisely with the carriage doors and only open when the train comes to halt so that no one can fall or jump onto the tracks. It is now erecting barriers on its railway bridges. In Australia, Brisbane’s Gateway Bridge has one and in Hobart, the Tasman Bridge not only has barriers, but surveillance cameras and emergency telephones.

-

Other measures include restricting supplies of pharmaceutical drugs

to small quantities and making packaging more difficult to open. In institutional

settings removal of ligature points has been helpful as has the substitution of natural gas in households in the UK.

- If someone you know is in deep distress, it may be helpful to ask their family remove any items

which could be used in the event of a suicide attempt. See more about getting help at the end of this post.

2. INTERACTING WITH THE MEDIA

The media can help to create awareness about suicide but done incorrectly it can sometimes lead to copycat behaviour. For this reason guidelines have been established about how to report on it responsibly e.g. by not sensationalising suicides, especially celebrity suicides and to focus on those who have successfully overcome such feelings or who display help -seeking behaviour. The UK’s Samaritans Support Service has developed very detailed tips on to how to present such material in print, on television, in film, drama and literature. Lithuania monitors its media closely and asks for amendment if the guidelines have not been followed. Austria awards an annual prize for good reporting on suicide.

3. FOSTERING SOCIO -EMOTIONAL LIFE SKILLS FOR ADOLESCENTS

Because suicide is the fourth leading cause of death among young people,* the WHO has developed a comprehensive program for 10 – 19 -year -olds, Its “Helping Adolescents Thrive (HAT)”program teaches young people how to problem solve and manage stress. It trains educators and others involved with young people in say, youth centres or detention centres for displaced young people, how to recognise risk factors and warning signs, about creating a safe school environment – free of bullying and discrimination, how to foster positive social connections, healthy use of social media and so on, and forges links with support services and the wider community. As well as increasing awareness of signs of distress in oneself and others, it conveys information about what support is available. It also reduces the stigma associated with mental health and needing help. Read the full text here.

In 2009, the European Union funded a two – year research

program “Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe (SELYE)" to determine which school intervention programs

were most effective. This involved at 168 schools across 10 countries and 11,110

students. The “Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM)” program was found to be a clear

winner.

Young people who participated showed a 50% lower rate of suicidal behaviour and new cases of moderate to severe depression were also reduced by 50%. It emphasises peer support, empathy towards others and how to go about seeking help. It also helps to change students’ perceptions about mental health and makes them more resilient in the face of adverse life events. The program has since been commercialised in collaboration with Sweden’s Karolinska Institute as Mental Health International and has been taken up or trialled in many countries throughout the world including Australia, India, the USA and Europe with some 100,000 students having taken part. Read more here.

4. EARLY IDENTIFICATION, ASSESSMENT, MANAGEMENT AND FOLLOW -UP

Among the benefits of large projects such as SELYE, is that researchers learned

a great deal about youth behaviour and how to identify individuals and groups

who may be more at risk than others. There are other forms of early recognition

too. Japan for instance, immediately refers people to the Health Sector if they

visit the Social Welfare Department with financial difficulties for example. People

experiencing physical or mental health conditions are also at greater risk and

should be identified by their health professionals for special attention.

The Islamic Republic of Iran has developed a smooth pathway via local GPs for early treatment for those experiencing depression.

Assessment and Management is more for professionals in the field. The Republic of Korea has expanded its emergency department from 25 locations in 2013 to 85 locations in 2020 as part of its revised National Suicide Plan.

Providing

multidisciplinary reviews after a suicide led to a reduction in suicide in clinical

populations in England and Wales.

Follow -up is important both for those who have attempted suicide and anyone affected by it, including those helping others through a crisis. Besides formal follow – up by Health Departments and the like there is an increasing role for the meaningful participation by such "survivors' in community support either as volunteers in crisis centres, in self – help groups and in providing input into programs and policies involving those at risk of suicide. See for example “Roses in the Ocean” an Australian organisation or Scotland’s Lived Experience Panel.

Canada has recently instituted a program whereby those who counsel others also have a chance to discuss their experience with other facilitators for mutual support, to share successes and failures and to promote best practices in prevention. This has proven especially beneficial for those working in isolation.

Decriminalising and Destigmatising Suicide

Not specifically mentioned in the WHO literature, but mentioned by the Guardian, is the fact that suicide remains illegal in some 20 countries and a further 20 countries ban it on religious grounds. This makes it very difficult to assess the extent of the problem and also makes it very difficult for those affected to seek help.

* Sadly, the suicide rates for older people are even higher at 24.5% for those over 70 and 14.25 % for people between 50 and 69, but they hardly rate a mention because they are overshadowed by deaths from other causes such as cardio - vascular disease and cancer in higher age groups.

WHERE TO GO FOR HELP AND SUPPORT

If you or anyone you know is experiencing distress call your local helpline. Some are listed below. Find out what yours is and put it in your phone or on your fridge. You may never need it, but someone else might. In extreme cases, just call your local emergency number or go to your nearest hospital.

AUSTRALIA: Lifeline 13 11 14

USA: 1-800-SUICIDE

National Suicide Prevention Hotline 1 -800 -275 -8255

CANADA:

Canada Suicide Prevention Service 1-833-456-4566

Connex Ontario 1-866-531-2600.

UK: The Samaritans 116 123

INDIA: 99220-01122/99220-04305

A LIST OF INTERNATIONAL HELPLINES CAN BE FOUND HERE

There are also specific ones for specific groups or issues. For example the USA has one for the LGBTQIA community and you can text many of them too. See more about using Hotlines here.

Next time we'll be returning to our discussion about Age - friendly cities.

Comments